Part I – Introduction

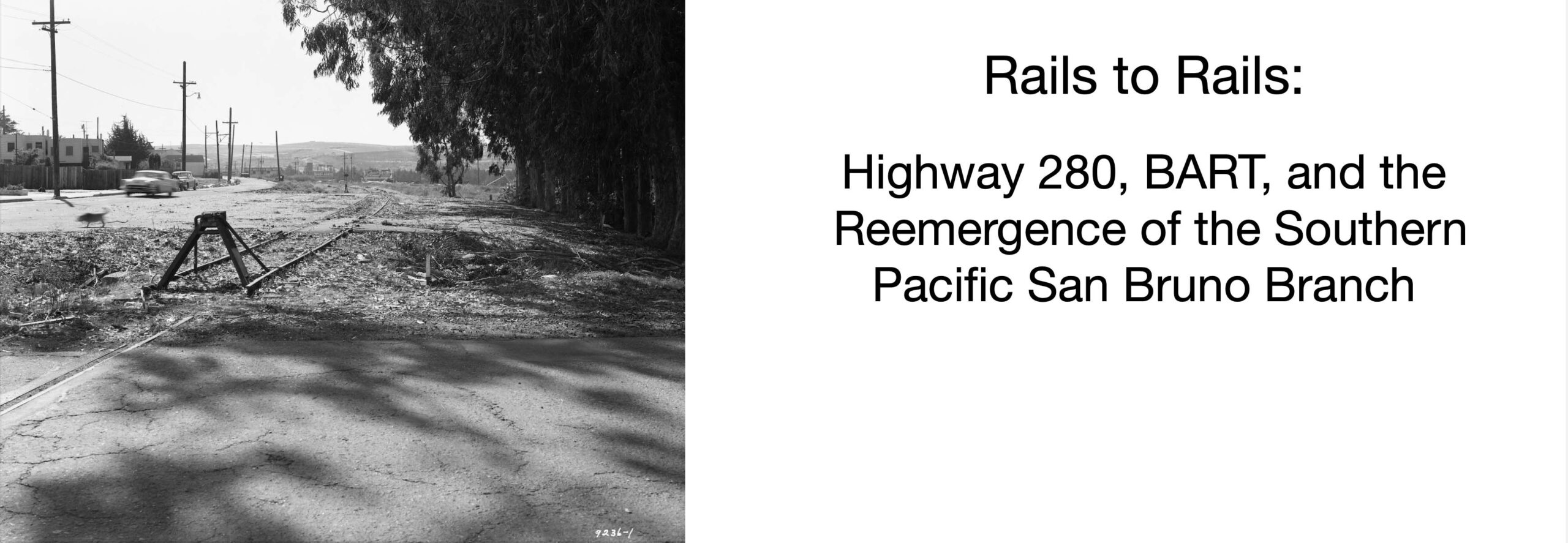

If this southwest view from the abandoned San Mateo Ave. grade crossing of the Southern Pacific, SP, San Bruno Branch from Oct. 16, 1962 is unfamiliar, its legacy dates back to 1864, when the transformative San Francisco and San Jose Railroad, SF and SJ, began regular service between San Francisco and the Peninsula. By the end of that decade, the SP would have purchased the route.

L279-05-Copyright California Department of Transportation, 9236-1, (Image 1 of 47)

BART’s original three East Bay lines relied on preexisting adjacent right-of ways with active track for their construction; left, the Western Pacific Zephyr in Hayward on Mar. 19, 1970; center, on the test track in Concord along the Sacramento Northern in 1965; right, by the El Cerrito Del Norte Station with a passing Santa Fe freight from Apr. 21, 1979. Credits: left, Victor Du Brutz Photo, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 80704wp; center, John Harder Photo, Courtesy John Harder; right, Ron Hook Photo, Courtesy Ron Hook.

L279-10-Multiple Attributions, (Image 2 of 47)

A comparable image to those seen for the East Bay for BART’s original Daly City line does not exist. On the left, Arthur Lloyd’s north view of SP 2652 and freight heading south from Elkton, today Balboa Park, on July 16, 1943, and the northeast view of BART on the right from Nov. 3, 1973. Balboa HS is seen in the background of each, but these trains are not on the same right-of-way. There is, however, a strong historical link between them, and a transition between their operation. Credits: Left, Arthur Lloyd Photo, 119031sp; Right, Herrington-Olson Photo, 135968BARTD

L279-15-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, (Image 3 of 47)

The creation of Highway 280 was the primary event impacting the SP to BART transition. The two maps indicate that after leaving its subterranean depths southwest of the Glen Park station, black dot, the BART route follows the general route of the former SP line. The evidence for this is lost today as construction of Highway 280 in the 1960s excavated the SP right-of-way before BART had finalized their route through San Francisco.

L279-20-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 172469, and Google Maps, (Image 4 of 47)

A second earlier event that would indirectly impact the SP-BART transition was the opening in Dec. 1907 of the SP’s Bayshore Cutoff or “Bayshore”, the latter name to be used in this review. Starting with one of many outstanding SP Valuation photos in the the Western Railway Museum Archives, this north view from San Bruno in 1923 shows the original line heading for the climb into San Francisco on the left or west, and the new Bayshore flat route along the bay on the right or east. The former mainline has been given several names since; “Old Mainline” as to its origins; “Ocean View” denoting its route; and “San Bruno Branch” to specify its final function for the SP. The latter will be used in this presentation given that term’s physical and temporal relation to BART, or it will be denoted as the “original route”.

L279-25-SP Valuation Photo 428-V, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 75116sp, (Image 5 of 47)

The Bayshore route out of San Francisco is indicated by the blue arrow versus that of the San Bruno Branch, green arrow, in the posted map from 1914, left panel, with a detail in the right panel. The lighter red lines display the streetcar competition within San Francisco for each route. For this project, several important references were consulted: “When Steam Ran on the Streets of San Francisco” by Walter Rice and Emiliano Echeverria, Harold E. Cox, Publisher; “Southern Pacific’s Coast Line” by John Signor; “The History of the San Francisco and San Jose Railroad”, a 1948 Master’s thesis from UC Berkeley by Louis Richard Miller; and “SP San Bruno Branch (old main line)”, a well referenced essay by Henry Bender.

L279-30-Rand McNally and Co., David Rumsey Map Collection, D. Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries, (Image 6 of 47)

Using primarily information from the referenced sources, the table to the right was compiled to realize the overall advantages gained by SP President E. H. Harriman’s very expensive and forward thinking project, one that was able to withstand the 1906 earthquake. Starting at San Bruno, the Bayshore included five tunnels accounting for almost 20 percent of the total mileage, one permanent trestle, and a cut at Visitacion Point that John Signor noted was 95 feet in depth, and required removal 750,000 cubic yards of earth. The earth was put to good use to fill in Visitacion Bay and the 2.5 mile temporary trestle completed in 1905, shown in the left south view on May 8, 1905. As reported by the San Francisco Call, Vol. 103, No. 8, Dec. 8th, 1907, the total cost was said to be 7 million dollars, equivalent to 222 million dollars in 2022 determined by https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation.

L279-35-C. M. Kurtz Photo, Courtesy John Signor, Table by Stuart Swiedler, (Image 7 of 47)

This 1923 southeast view from 26th and Wisconsin Sts. in San Francisco shows the Bayshore’s 3660 ft. timber trestle with steel overpasses spanning Islais Creek and local streets. Although deemed to be permanent in 1907, based on aerial views, this trestle was filled in between the 1950s and 1974. For an extensive well-referenced on-line article on the Bayshore, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bayshore_Cutoff

L279-40-SP Valuation Photo 110-V, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 72176sp, (Image 8 of 47)

The partial schedules reproduced here show the transfer of San Jose-San Francisco passenger service to the new Bayshore route. More history: Miller’s original source documents explain that the Bayshore route was favored over the original route through Ocean View from an engineering prospective, avoiding grades, cuts and fills, but inferior in terms of population along the tracks. Rice and Echeverria point out that the Ocean View route had the potential for revenues from “a racetrack, local farms, resorts and amusement areas.”

L279-45-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 14307sp, top, 14308sp, bottom, (Image 9 of 47)

The San Bruno-San Francisco portion of the 1908 schedule shown here reveals that the San Bruno Branch was primarily reduced to a few truncated “loop” routes tied to the Bayshore route. There is no indication of any trains originating from San Jose. Gasoline-powered McKeen cars operated on the rails in the 1910s, but historical accounts differ on the details. More history: Rice and Echeverria map out a spur just north of Daly City, then called Spring Valley, to bring passengers to Ingleside Race Track in 1895, and a freight track that split off to Lake Merced supplying north along the coast. The Ingleside Coursing Park dog track would be added nearby, but the Market St. Railway streetcars, a subsidiary of the SP since 1893, soon outcompeted its parent. Historical accounts differ as to their end, but racing operations had ceased by the time of the earthquake of 1906.

L279-50-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 14308sp, (Image 10 of 47)

Several authors state that the San Bruno Branch continued passenger service into the early 1930s. Employee timetables between 1915 and 1930 were not readily available, but the one shown here from 1928 shows a single train a day except Sundays in each direction at a very early hour. Passenger trains were no longer listed along the route in timetables by May 3, 1931. Henry Bender cites California Railroad Commission Decision 22212 from 1930. Rice and Echeverria review of 1913 to 1925 is consistent with a progressive loss in passenger service, losing out to the more frequent and less expensive Market Street Railway no. 40 streetcar line between Market St. and San Mateo. Based on the Peck-Judah Blue Book from 1925, they claim all passenger service ended in 1925, but technically the image shown here suggests otherwise, the hours of operation probably more linked to newspaper and mail delivery.

L279-55-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 14318sp, (Image 11 of 47)

The timing of abandonment on the branch line can be approximated by reviewing employee timetables, the three here going right to left covering the period of the loss of passenger service on the entire branch, to the loss of freight service in the section through the Mission District. The date of the latter was documented by Rice and Echeverria as Aug. 10, 1942, consistent with the two timetables shown here, center and left.

L279-60-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, (Image 12 of 47)

These three employee timetables, right to left, indicate that freight service northeast of Elkton did not survive into the 1950s. The latest timetable into the 1950s is shown on the far left, but no timetables between this 1957 date and the ICC filing to shut down the branch north of Daly City were found to pinpoint the last day a train headed over the Ocean View summit. Refs: http://www.vasonabranch.com/railroad/timetables/index.html; https://wx4.org/to/foam/maps/and_timetables4.html

L279-65-Multiple Attributions, (Image 13 of 47)

This not-to-scale timeline summarizes important dates contrasting the abandonment of sections of the San Bruno Branch versus the development of BART. To visualize the transition in 2022, the timeline lines up the San Bruno Branch stops at Bernal and Elkton with BART’s Glen Park and Balboa Park, respectively, appreciating these stations were close to one another, but not coincident. The remainder of this presentation will focus on the section between 3rd St. and Townsend and the Bernal stop.

L279-70-Graphic by Stuart Swiedler, (Image 14 of 47)

A northeast view from Mar. 1950 delineates the territory covered by the original route, left panel, shown where the double-track headed down Harrison St. has separated from other local freight sidings at Mariposa St., yellow arrow. The detail on the right shows the point at Townsend and 7th Sts. where the two tracks of the original route separated from those to the Bayshore and headed along Division St. The tracks survived until just about 1990, while Seals Stadium was demolished in 1959. The surviving brewery building at no. 1550 Bryant Street was remodeled in the mid-1980s after several ownership changes and occupation by punk rock bands.

L279-75-Copyright California Department of Transportation, 1677-1, (Image 15 of 47)

One more detail from the northeast view from Mar. 1950 where the tracks curved from Division St. to Treat Ave., along where shops of the SP had once operated in San Francisco until the Bayshore was opened.

L279-80-Copyright California Department of Transportation, 1677-1, Detail , (Image 16 of 47)

One more view to the north from Mar. 1950, Harrison St. can be seen along the left or west edge with many sidings to local businesses. The yellow arrow points to a yard that Rice and Echeverria note was to service local industry post-Bayshore, the location of the 18th St. stop. The area boxed in red in the middle image is shown enlarged on the right, the blue arrow pointing to the end of the railroad’s double-track on Harrison St., just north of 19th St. John Signor noted that the SP never had a franchise along Harrison St., and their plans to double track from this point through the Mission was opposed and prevented by the residents.

L279-85-Copyright California Department of Transportation, 1677-10, (Image 17 of 47)

The SP ran freights from downtown to this spot at 23rd and Folsom Sts. until about 1990, the portion through the Mission from this point east to Miguel St. having been abandoned on Aug. 10, 1942. In 2022, contrast the community park between Treat Ave. and Folsom St. versus the unresolved ownership of the portion between Folsom and Harrison Sts., Parcel 36. The details of the this parcel are provided in an excellent essay by Elizabeth Creely that can be found at https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=Forgotten_Railroad_Right-of-Way_at_22nd_and_Harrison

L279-90-Courtesy Google Maps, (Image 18 of 47)

Going back in time, the left panel shows the Sanborn Map Company, 1914 - Dec 1950 Vol. 6 diagram of the right-of-way between Harrison and Folsom Sts. The two pasted-over areas enclosed in red cover the name J.H. Kruse. On the right, the detail from the 1938 aerial reveals the area was definitely involved in lumber and utilized SP spurs. John Henry Kruse first appeared in directories in 1857 selling wood, coal, hay and grain at 24th. and Harrison Sts. Refs: Left, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, Sanborn Maps Collection; R, Harrison Ryker Photo, David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries

L279-95-Multiple Attributions, (Image 19 of 47)

Same comparison as previous, but here Ricci-Kruse appears. By 1880, Kruse was at 23rd and Shotwell Sts., and by 1890 had expanded to lumber and hardware. The business survived under the Kruse name as Ricci-Kruse with retail at no. 912 Shotwell, just south of 23rd St. in 1957, but would fade from the Mission with the abandonment of the San Bruno Branch in San Francisco in 1958. The wholesale business would move out to South Basin north of Candlestick Point. Refs: Left, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, Sanborn Maps Collection; R, Harrison Ryker Photo, David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries

L279-100-Multiple Attributions, (Image 20 of 47)

Next for a ride on the original route in the Mission in 1923. This north view shows the singe track from Harrison St. crossing 22nd St. with double crossing gates for car and pedestrians, respectively. The Ford factory with spur track is seen north of 22nd St. The building would house the Samuel Gompers Trade School in 1946, and the site has been occupied by George Moscone Elementary School since 1980. In addition to the spur, the train had a station designated as “Ford” as shown in the previous 1930s employee timetables.

L279-105-SP Valuation Photo 150-V, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 72227sp , (Image 21 of 47)

A northeast view from 1923 features Treat Ave. back to Harrison St., mentioned previously as Parcel 36 in 2022. The insert from the 1923 Crocker Langley Directory documents Kruse’s presence from Harrison to Shotwell Sts. The detail on the right shows the crossing gates and Carnation sign seen in the previous image, and also a small shelter and the sign indicating 2 miles to 3rd St. and Townsend. The Western Railway Museum has several views of the Kruse operation.

L279-110-SP Valuation Photo 155-V, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 72232sp, (Image 22 of 47)

The southwest view with detail from 1923 of the Mission St. crossing between 24th and 25th Sts. illustrates why adding a second track though the Mission was not a practical option for the SP. Imagine the congestion, smoke and noise from triple-headed steam locomotives. Rice and Echeverria note that train speeds through these mid-block grade crossings were limited to 15 miles per hour. Note the double set of crossing gates on each side of the street, and the many additional ones for subsequent alleys shown on the right. Digging below this crossing in 2022 would provide access to the BART 24th. St. station.

L279-115-SP Valuation Photo 175-V, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 72252sp, (Image 23 of 47)

Ahead to 1941, and a northeast view from Valencia St. toward Mission St. shows one crossbuck, but the crossing gates are gone, left. Likewise, the same findings from Valencia St. looking southwest towards San Jose Ave., right. The track is in bad shape and overgrown. The original terminus of the SF and SJ, the SP did have a small depot at Valencia St., but maps between 1890-1915 differ as to location, the northeast or southwest corner of the intersection with 25th St., independent of the date. The latter corner is an empty lot as seen in the right image, confirmed by Ryker’s 1938 aerial, a more likely place for the building.

L279-120-Louis R. Miller Photo, Courtesy University of California, Berkeley, (Image 24 of 47)

The angling cut also created issues when emerging at street intersections, left, at 26th St. west of Guerrero St., viewed to the northeast in 1923. Add the no. 10 streetcar and the extra track, to be addressed next, makes the tower’s presence understandable. Using Google maps to compress the surroundings, right, reveals the Lulu Laundromat at the northeast corner of the intersection in 2022, seen as D. Del Buono Fancy Grocery, left. The red arrow is a reminder that the right-of-way between Guerrero St. and San Jose Ave. has been preserved as Juri Commons, a freely open corridor from the original route.

L279-125-SP Valuation Photo 187-V, Courtesy BAERA, W. R. M. Archives, 72270sp, and Google Maps, (Image 25 of 47)

The double track segment here could be traced back to Sanborn maps to 1905, and there was no specific industry, the northern-most track clearly a siding. It is conceivable that the railroad used this siding to serve the general area as they did at 18th St. and Harrison Sts., or it could have facilitated two-way traffic. None of the other sources or images found provide an answer. The siding joined the mainline just east of the Dolores St.-27th St. overpass, bottom left. Ref: Left, San Francisco, Sanborn Map Company, Panel 737, 1914 - Jan. 1950. Vol 7, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, Sanborn Maps Collection; Right, Harrison Ryker Photo, David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries

L279-130-Multiple Attributions, (Image 26 of 47)

The last section through the Mission and Noe Valley utilized overpasses as shown in the Ryker’s 1938 aerial turned 90 degrees clockwise such that north is to the right and south to the left.

L279-135-Harrison Ryker Photo, David Rumsey Map Collection, D. Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries, (Image 27 of 47)

This south view from 1923 down Dolores St. at 27th St., left, explains the need for the overpasses to avoid the precipitous drop in grade to the south. The image on the right from 1941 from the southwest side provides a northeast view. Credits: Left, SP Valuation Photo 191-V, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 72272sp; Right, Louis R. Miller Photo, Courtesy University of California, Berkeley

L279-140-Multiple Attributions, (Image 28 of 47)

The next three overpasses over Duncan, 28th and Valley Sts, north to south, respectively, had steel supports with walls that encased the inner wooden trestle structure. This north view is from the overpass over Valley St. in 1942. Credit: Robert H. McFarland Photo, Robert H. McFarland Collection via David Gallagher

L279-145-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 193907sp , (Image 29 of 47)

Robert McFarland most likely turned around from where he took the previous image to face south, and documented the overpasses at 29th, Day and 30th Sts., foreground to background, that did not have walls above the tracks. Why they differed from the ones to the north has not been investigated. The house to the right or west of the 29th St. overpass is 265 29th St., the distinctive, two-level Edwardian house with the round columns at each end, and still around in 2022. Credit: Robert H. McFarland Photo, Robert H. McFarland Collection via David Gallagher

L279-150-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 93915sp, (Image 30 of 47)

This east view on 30th St. with SP overpass from Chenery St. toward Mission St. shows the tracks for the Market Street Railway no. 10 and no. 26 lines are filled in, but the overhead wire remains, left. For dating purposes, the line was abandoned on Apr. 15, 1942, and the cars in view have 1942 license plates. The southwest view on the east side of the 30th St. overpass, right, shows the gentle descent of the right-of-way to where it blocked Dolores St. and San Jose Ave., just north of Randall St. The presence of a Market Street Railway no. 9 streetcar was explained by Bay Area rail historian Grant Ute as follows; “the no. 9 line had several outer terminals in the period Jan. 15, 1939 to June 23, 1940, one of which was running along the no. 26 line to Daly City. Thus it transited Mission St., 29th St., San Jose Ave., 30th St, Chenery St., Diamond St. to San Jose Ave.”

L279-155-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 194527msry, l, 194530msry, r, (Image 31 of 47)

Before settling in to the Bernal Cut south of Randall Ave., the right-of-way skirted venerable Fairmont School, seen in a southwest view from 1942. The school was established in 1864, but moved and experienced growing pains until this brick structure opened in 1917, lasting 60 years until razed for the next version. The name of the school was changed to Dolores Huerta Elementary School in 2018. See https://www.glenparkhistory.org/single-post/2015-4-8-origins-of-the-fairmount-school. Credit: Robert H. McFarland Photo, Robert H. McFarland Collection via David Gallagher

L279-157-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 193911sp , (Image 32 of 47)

Another view of the school, this time to the northeast in 1942. The image captures the up and down topography of Dolores St. The large overpass at 27th St. can just be made out in the distance. Credit: Robert H. McFarland Photo, Robert H. McFarland Collection via David Gallagher

L279-158-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 93917sp, (Image 33 of 47)

A subject that remains unanswered is the transition of the cut in the Mission and Noe Valley to houses, save the few sections preserved and a few parking lots at corners. With the red arrow marking the entry of rails from Harrison St. across 22nd St., these three panels show that a significant amount of the cut still persisted in 1956, fourteen years after abandonment. Credits: Left, R, Harrison Ryker Photo, David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries; Center, gs-vlx_1-89, Courtesy of UCSB Library Geospatial Collection; Right, Courtesy Google Earth

L279-160-Muliple Attributions, (Image 34 of 47)

One initial way the abandoned cut was hidden from view was the placement of billboards that filed the space. Here from Mar. 24, 1945 is a south view to Bernal Heights from Mission St. between 24th and 25th Sts., left. The center and right enlargements from that image show the billboards.

L279-162-Moreau Collection, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 172087msry, (Image 35 of 47)

Louis Miller in his Master’s thesis wrote that all track and overpasses in the Mission and Noe Valley were removed in 1942. A familiar northeast view from Guerrero St. toward Valencia St. in 1942 with siding track, left, and a rubble-strewn northeast view in 1947, shows no progress toward development. Recall, this section would become Juri Commons. Credits: Left, Robert H. McFarland Photo, Robert H. McFarland Collection via David Gallagher, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 193816sp; Right, Louis R. Miller Photo, Courtesy University of California, Berkeley

L279-165-Multiple Attributions, (Image 36 of 47)

The most difficult of these structural alterations was eliminating any trace of the Dolores St. overpass in 1942, which after removal of the steel structure by something approaching surgical precision, left, was quickly followed by demolition of the abutments and berm to Duncan St., right. More research needed to describe the details of the demolition and redevelopment of the entire section in the Mission and Noe Valley. Credit: Left and Right: Robert H. McFarland Photo, Robert H. McFarland Collection via David Gallagher

L279-167-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 193816sp, l, 193819, r, (Image 37 of 47)

Shown here is the Bernal Cut private right-of-way looking southwest in 1923 from the Charles St. bridge toward the steel Miguel St. bridge, the latter noted in some sources as the southern boundary of the 1942 abandonment. Creating the cut was the original routes biggest challenge north of San Bruno. The Daily Evening Bulletin, Mar. 25, 1963, p. 3, noted “but by March the grading obstacle at Bernal Heights had been overcome. It was 2,700 feet long and 43 feet deep in the deepest portion.” By 1930, the cut would be widened to 117 feet as indicated on the 1937 map. More next. Credits: Left, SP Valuation Photo 216-V, 71681sp; Center, BAERA 128864; Right, BAERA 172469

L279-170-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, (Image 38 of 47)

Further southwest, the next view from 1923 of the cut shows that its western border came to an end at about St. Mary’s Ave. The detail on the right shows the area the railroad designated on timetables as Bernal. The two buildings to the left or south of the isolated boxcar was listed in the 1925 Crocker Langley Directory as indicated in the insert, as Ray Burner Co. in 1935, and Ray Oil Burner Co. in 1950, a San Francisco fixture until the end of the century. By that point, Bernal Ave. had been renamed San Jose Ave.

L279-175-SP Valuation Photo 223-V, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 74955sp, (Image 39 of 47)

Finally at Bernal, just about where Cuvier St. met the tracks, shown here is a southwest view from 1923. Up the ways are the two buildings for Ray Oil Burner.

L279-180-SP Valuation Photo 230-V, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 74955sp, (Image 40 of 47)

Rice and Echeverria note that a 1927 bond issue allowed the city to widen the cut. Shown here is the 1926 proposal by City Engineer Mike O’Shaughnessy’s Office prepared for the Municipal Railway from the 1926-27 Annual Report of the Bureau of Engineering of the Dept. of Public Works, City and County of San Francisco. The plan would accommodate pedestrians, four lanes of auto traffic, two tracks for electric streetcars, and two tracks for a SP electric interurban train. The streetcar tracks made their debut in 1991, and the SP plan never materialized.

L279-185-Ted Wurm Collection, Courtesy BAERA, WEstern Railway Museum Archives, 17478Muni, (Image 41 of 47)

Shown here on the left is the Bernal area from the Sanborn Map Company, Panel 912, 1915 - Mar 1950, and to the right a corresponding detail rotated 37 degrees clockwise from Ryker’s 1938 aerial. The red arrow indicates the eastern end of a railroad siding, and the insert shows a detail of the take-off of a spur track across Bernal Ave. to Ray Oil Burner Co. The widening process would remove many houses and structures, and the buildings for Ray appear to have a different shape than shown previously. Additional images at the Western Railway Museum show some of these houses. See https://www.bernalcut.org/history

L279-190-Multiple Attributions, (Image 42 of 47)

Two images from 1941, starting on the left with a northeast view east of the Highland Ave. overpass. The sign in the distance is to advertise Lachman Home Furnishings, a business on Mission St. The right panel shows a southwest view from that overpass toward the Richland Ave. overpass, the replacement for the steel Miguel St. bridge. Given that the SP had no means to add a second track in the Mission, they never bothered to add a second track here after the cut was widened, save for one siding shown in the last panel. Credits: Left, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, Sanborn Maps Collection; Right, Harrison Ryker Photo, David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries

L279-195-Louis R. Miller Photo, Courtesy University of California, Berkeley, (Image 43 of 47)

If you want a visual marker to where the 1942 abandonment extended to in the cut, this southwest view from the Richland Ave. overpass shows the finish line. The post cut-widening version of Ray Oil Burner Co. with the arch-shaped windows can be seen to the left or south of the tracks in the distance. Credit: Left and Right: Robert H. McFarland Photo, Robert H. McFarland Collection via David Gallagher

L279-197-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 93895sp , (Image 44 of 47)

The previous image would suggest that the workers in this southwest view from 1942 are making the new northern end of the San Bruno Branch a more definitive marking. The location of this truncation allowed the spur to Ray Oil Burner Co. to remain in use. See the next detail.

L279-200-Photo AAA-9922, Courtesy San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, (Image 45 of 47)

A detail from southwest view from 1942 of the western end of the revised Bernal Cut shows, left to right, reveals the new building for Ray Oil Burner Co., with its arched windows facing the right-of-way, a structure that would last more than a half century. The switch track from the mainline to the building, and the end of the siding with boxcars can also be appreciated.

L279-205-Photo AAA-9922, Courtesy San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, Detail, (Image 46 of 47)

The introductory tour ends at the intersection of the SP tracks at Monterey Blvd., Joost Ave., and Diamond Sts., left to right, in a southwest view from Feb. 22, 1936. Ventilation grates for the BART Glen Park station replace Bernal Auto Reconstruction in 2022. Next time, setting the stage for Highway 280. Appreciation to Bay Area Rail historians Bob Townley and Grant Ute for sharing their knowledge and bringing to light important images and documents from the Western Railway Museum Archives, and Henry Bender for edits. For more must reads on the internet, see See https://www.nesssoftware.com/www/sf/sfsjrr.php; https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=Before_the_I-280_Freeway; https://sf.curbed.com/2013/5/29/10239534/the-lost-railroad-tracks-of-the-mission-and-noe-valley and references therein.

L279-210-Photo AAA-9896, Courtesy San Francisco History Center, San Franisco Public Library, (Image 47 of 47)