Part 7 – The Highway 77 Saga and Other Roads Not Created

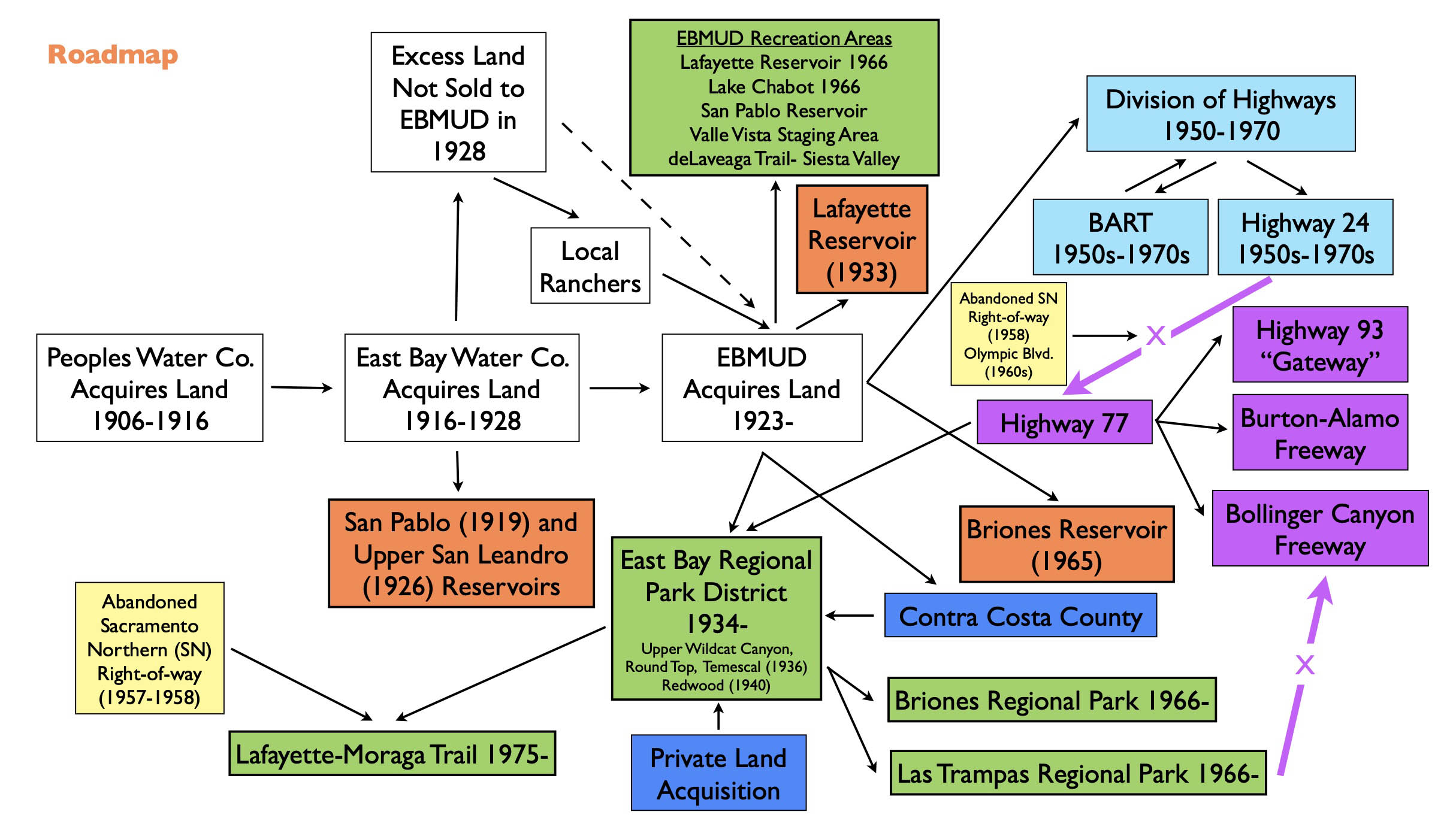

Having previously set down the footprint for Highway 24, the last element in the final configuration of Lamorinda pertains to roads contemplated, but never built. These projects are listed within the purple-filled boxes on the right side of the diagram.

L255-05-Compiled by Stuart Swiedler , (Image 1 of 31)

First, a consideration of three highways listed here. These contemplated connectors either traversed protected land, or one or both endpoints did not connect to a bonafide highway.

L255-10-Annotated 1980 AAA Map, (Image 2 of 31)

The Bollinger Canyon version was eliminated first as it bisected Las Trampas Regional Park and would have ended onto a two-lane road, St. Mary’s Rd. The Burton-Alamo version suffered the same limitation vis-a-vis St. Mary’s Rd., but was more unfavorable due to the many residents along its length.

L255-15-Courtesy Contra Costa Library, (Image 3 of 31)

As seen in this assessor’s map, the Burton-Alamo Highway was indeed highly favored. But its placement relied on something much grander, soon to be revealed.

L255-20-Courtesy DepartMent of Public Works, Contra Costa County, (Image 4 of 31)

The Gateway Highway project had much more going for it. The on and off ramps from Highway 24 were already in place as seen in this south view above Highway 24 from Aug. 22, 1973. As a catalyst, auto congestion on Moraga Way, red arrow, was becoming a more significant issue.

L255-25-Copyright California Department of Transportation, C4255-1 , (Image 5 of 31)

This two panel, disjointed southwest panorama from Aug. 22, 1973 starts at the north with Highway 24, right panel, and extends southward, left panel.

L255-30-Copyright California Department of Transportation, C4255-2 and 3, (Image 6 of 31)

Looking back at the northern section through which this road could be placed, it was devoid of any houses as seen in this north view toward the overpass of Highway 24, red arrow. This land would soon become a battleground for developers vs. environmentalist, but at this point it was pristine. See https://www.sfgate.com/green/article/A-DONE-DEAL-A-compromise-decades-in-the-making-2499331.php

L255-35-Copyright California Department of Transportation, C4221-4 , (Image 7 of 31)

Further south from the previous point as seen in this south view from July 24, 1973, there was a sprinkling of residences, and the Pacific, Gas and Electric Co. Moraga Substation, blue arrow, appreciating its location is actually in Orinda.

L255-40-Copyright California Department of Transportation, C4221-1 , (Image 8 of 31)

This second two panel, disjointed southwest panorama from Aug. 22, 1973 shows more residences to the south of the substation, left, versus those to the north, right.

L255-45-Copyright California Department of Transportation, C4255-5 and 6, (Image 9 of 31)

Further south, as seen in the west view from Aug. 22, 1973, Moraga Way has swung further west along the bottom of the image. Del Ray Elementary is seen to the north or right, and Miramonte High School, left, and in between the two on the ridge, the Moraga Adobe Homesite.

L255-50-Copyright California Department of Transportation, C4255-4 , (Image 10 of 31)

Two northwest views of the Gateway Valley taken from Moraga on July 24, 1973 are presented here. The left panel was taken above Moraga Rd., while the more detailed right panel shows no structures or golf course as yet for the newly founded Moraga Country Club. The question is, if a Gateway Highway had been built, where would its southern exit point have been?

L255-55-Copyright California Department of Transportation C4221-2 and 3, (Image 11 of 31)

This west view of the western rim of Moraga just reviewed has the area for the future country club demarcated by a heavy white line, and includes a highway with interchanges with Moraga Way to the right, and the Moraga Rd.-St. Mary’s Rd. split to the left. The highway appears west of Miramonte HS and any housing existing to the west of it. This overlay was dated Nov. 29, 1965. Should we be surprised by this bold vision?

L255-60-Herrington-Olson Photo 8-13210, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum, 132236cv , (Image 12 of 31)

This California Division of Highways map from 1960 shows the Gateway Highway, gold arrow, connecting to another road, green arrow, coming in from Route 50 in Alameda County. Note the presence of the Burton-Alamo route, black arrow, clearly linked to road coming in from the west, obviating the need for St. Mary’s Rd.

L255-65-David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries, (Image 13 of 31)

Ahead to 1965, and the road through Gateway Valley is now labeled Highway 93, extending all the way to Richmond and Alamo, and the highway from Alameda is now Highway 77, the latter heading all the way to Pleasant Hill.

L255-70-David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries, (Image 14 of 31)

By 1975, this map from the recently created California Department of Transportation shows a truncated Highways 77 to Highway 24 at its northern end, while Highway 93 no longer includes the Burton-Alamo Highway. The links to these maps and more detailed history were provided by http://www.gribblenation.org/2020/04/paper-highways-unbuilt-california-state_23.html

L255-75-David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries, (Image 15 of 31)

This south view at the Pleasant Hill Interchange with Highway 24 that was used to conclude the last update now has context. The Division of Highways added the complexity to the interchange even with the absence of a main route to the south, anticipating the later addition of the link to Highway 77. Now for some important historical background.

L255-80-Copyright California Department of Transportation, 5208-14 , (Image 16 of 31)

The story of Highway 77 in some ways starts with this ad in the Sept. 14, 1924 Oakland Tribune. The bottom right corner indicates that the developer of Forest Park is Wickham Havens, Inc. Haven’s father Frank was a partner with Borax Smith in the Realty Syndicate until they dissolved their partnership around 1910, after which Frank continued delivering water to Oakland and planted a significant number of the non-native Eucalyptus trees in the Oakland hills.

L255-85-Courtesy Oakland History Room, Oakland Public Library, (Image 17 of 31)

By 1925, Wickham Havens had an office at 1510 Franklin St. in Oakland. Between 1910-1920, he drove the development in Oakland of Haddon Hill, Havenscourt, Crocker Highlands, and the initiation of Lakeshore Highlands or Trestle Glen, and helped bring the Southern Pacific’s Oakland, Alameda and Berkeley Electrics and Key Route interurbans to those parts of Oakland.

L255-90-Cheney Photo H1938 and H1939, Oakland Cultural Heritage Survey, Oakland City Plan. Dept., (Image 18 of 31)

Havens played a large role in reorganizing the Oakland Real Estate Board in 1916, and served as its president from 1918-19. He was a director of Frank Havens’ the People’s Water Company in 1909. Newspaper accounts also reveal his dealings with members of the Realty Syndicate during his father’s tenure there, but he was not directly part of the realty firm.

L255-95-Cheney Photo H2121, Oakland Cultural Heritage Survey, Oakland City Planning Department , (Image 19 of 31)

Havens definitely profited by the sell-off of many of Borax Smith’s assets in Oakland and Piedmont in 1913, and was somehow involved in getting construction of the Claremont Hotel restarted after it had stalled in 1909. He produced promotional films, the one from 1928 is on the internet at https://archive.org/details/OaklandC1928. More about Forest Park in the update “Wickham Havens and Forest Park” in Landmarks section.

L255-100-Cheney Photo H2074, Oakland Cultural Heritage Survey, Oakland City Planning Department , (Image 20 of 31)

After reviving the original Forest Park development that had been stalled for 25 years, Havens shifted his focus to Shepherd Canyon and the areas that fed into it with three additional efforts as listed. Southwest view, circa 1925. The insert is from “Tract List for Northern Alameda County Complied for Ancestors Anonymous by Quentin.”

L255-105-Cheney Photo H2144, Oakland Cultural Heritage Survey, Oakland City Planning Department, (Image 21 of 31)

Before development in the canyon could get started, Park Blvd. needed to be extended beyond what is today Paso Robles Dr., the site of the Sacramento Northern Havens Station, green arrow.

L255-110-Central National Bank Map, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 83537, (Image 22 of 31)

Without a concern of connecting to the existing part of Park Blvd., Havens and Louis Saroni instead brought a road down from the Forest Park development ca. 1925 as shown in this before-and-after comparison. Ref: H2149, Oakland Cultural Heritage Survey, Oakland City Planning Department; H2224, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 26081sn

L255-115-Eston Cheney Photos H2149 and H2224, (Image 23 of 31)

The road was extended east, however, opening new possibilities for a connection with Contra Costa County. Northeast view, circa 1925.

L255-120-Eston Cheney Photos H2178, John Bosko Collection, Courtesy John Bosko, (Image 24 of 31)

By Jan. 1926, Havens made his intentions known to create a Victory Highway through the canyon to connect Alameda County to Contra Costa County. The initial road he built is presumed to be the present Scout Rd. in an effort to make a direct connection with Park Blvd. across Mountain Blvd., still not accomplished in 2021. Sequoia Park is now part of Joaquin Miller Park. See https://localwiki.org/oakland/Camp_Dimond%2C_Boy_Scouts_of_America

L255-125-Courtesy Oakland History Room, Oakland Public Library, (Image 25 of 31)

Evidence is presented here from Apr. 1926 to document the populous’ interest in constructing the Victory Highway.

L255-130-Courtesy Oakland History Room, Oakland Public Library, (Image 26 of 31)

By the end of 1927, the advantages for a route through Shepherd Canyon versus that of the existing Broadway Tunnel were made known in announcing another step to construct the new tunnel.

L255-135-Courtesy Oakland History Room, Oakland Public Library, (Image 27 of 31)

By mid-1928, both counties began seriously considering a new connection.

L255-140-Courtesy Oakland History Room, Oakland Public Library, (Image 28 of 31)

A closer look shown here from the article presented in the previous panel shows that tunnels through Temescal and Shepherd Canyon were favored choices.

L255-145-Courtesy Oakland History Room, Oakland Public Library, (Image 29 of 31)

Anticipating a tunnel through the eastern end of Shepherd Canyon, Wickham Havens was openly routing for its construction.

L255-150-Courtesy Oakland History Room, Oakland Public Library, (Image 30 of 31)

The obituary of Wickham Havens in the Oakland Tribune noted that he died on Nov. 25, 1934 at age 58 after a protracted illness that had led him to move to Moraga. The tunnel through Shepherd Canyon would not be built in favor of the one shown through Temescal in this east view of the new portal on Nov. 29, 1937, one week prior to its opening. His quest for a Shepherd Canyon highway and tunnel would return in the form of Highway 77, to be continued …

L255-155-Nickerson Photo, Copyright California Department of Transportation, 454-6, (Image 31 of 31)