Water in the 20th Century – Private-to-Public, Part I – Water Wars

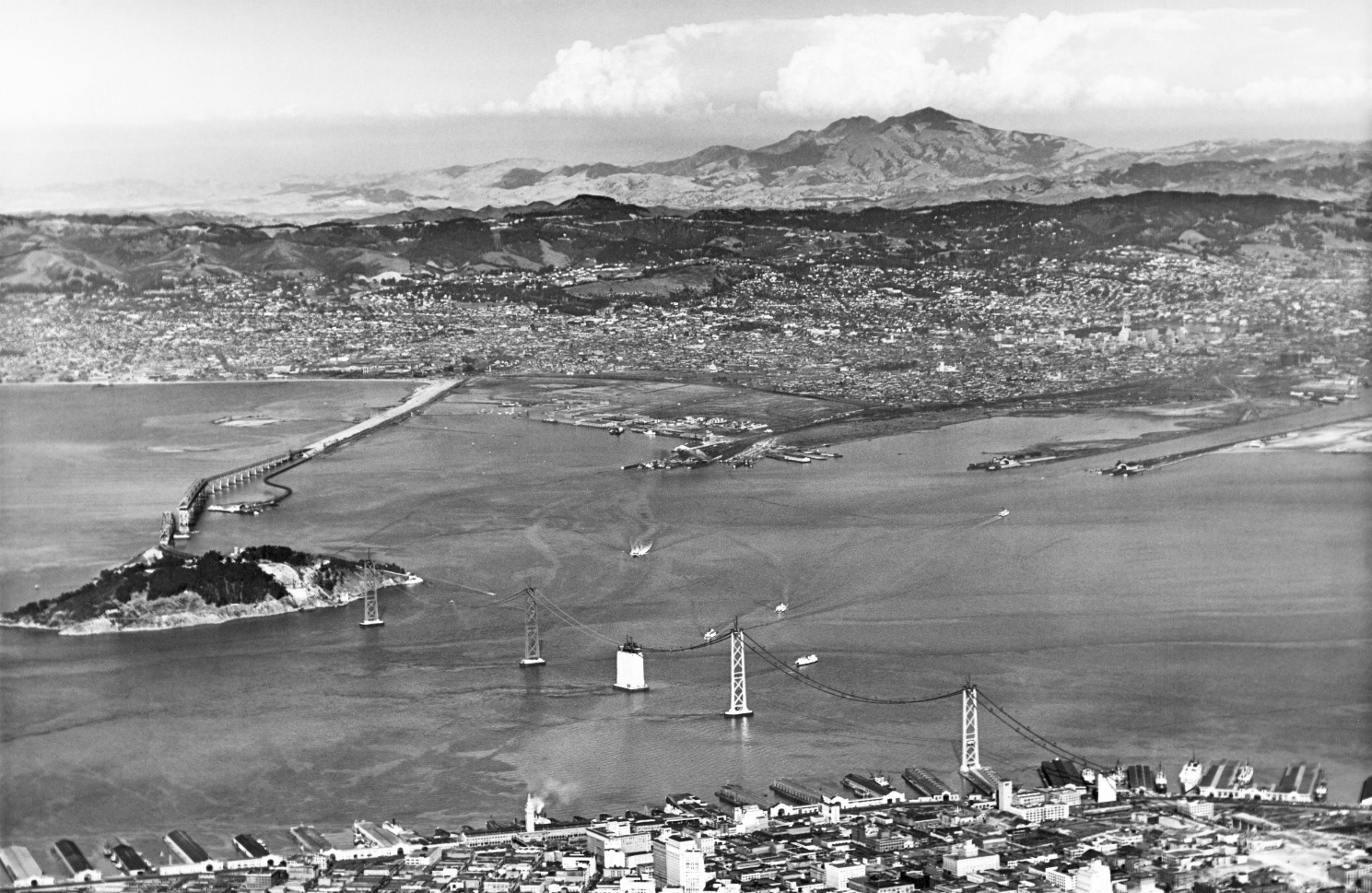

Water in the 20th Century will illustrate the impact of water on Northern California. Emphasis will be placed on public-to-private, eminent domain, riparian rights, reclamation, flood control, and navigation, while integrating aspects of agriculture along the way. A path from Oakland to Chico will be followed. East view of East Bay, circa 1935. Ref: 112 Kearny St, Cal Toll Br. Auth., EBRPD.P25.1

L191-01-B.W. Hellings Photo, Courtesy East Bay Regional Park District, (Image 1 of 40)

Water history prior to 1930 in the East Bay is murky and inconsistently recorded. The two major sources consulted for this first review are John Wesley Noble’s “Its Name Was M.U.D.” published by EBMUD, Oakland, CA, 1970, and “Ground Water Study and Water Supply History of the East Bay Plain, Alameda and Contra Costa Counties, CA” by S. Figuers of Norfleet Consultants, Livermore, CA, June 15, 1998. Available on-line at www.waterboards.ca.gov. Northeast view of Briones Reservoir, 2017.

L191-05-Stuart Swiedler Photo, (Image 2 of 40)

The Bay Area was in the sixth or seventh year of a horrible drought when this image was taken in Sept. 1923. Months before, voters from San Leandro to Richmond approved the Municipal Utility Act of 1921 to create the East Bay Municipal Utility District, EBMUD. In 1924, voters approved 39 million dollars in bonds to build Pardee dam and a 94-mile aqueduct from the Mokelumne River.

L191-10-Eston Cheney Photo W-338, John Bosko Collection, Courtesy John Bosko, (Image 3 of 40)

Our streets still provide evidence that the ownership and oversight of the water prior to EBMUD was in private hands. All water came from local sources, and the product at times was either not available or not worth drinking. Attempts in 1905 and 1914 to create a public water utility had failed the popular vote, but EBMUD meant the beginning of delivery of Sierra-derived water.

L191-15-Stuart Swiedler Photos, (Image 4 of 40)

In 1927, voters approved 26 million dollars in bonds for EBMUD to build local infrastructure from scratch or acquire the privately owned East Bay Water Company, EBWC. An easy choice, acquisition of EBWC with its water delivery system, 40,000 acres of watershed, and five East Bay dams was completed on Dec. 8, 1928. Sierra-derived water arrived to San Pablo Reservoir in June of 1929, but it did not fill until the following May. Ref: G4364.R6 1951 .T38

L191-20-Courtesy Earth Sciences and Map Library, University California, Berkeley , (Image 5 of 40)

The 1953 boundary in the previous map preceded Briones Reservoir, the largest of the East Bay reservoirs, completed in 1964 and shown here during construction in a northeast view from Aug. 1963. Despite having less watershed land than Lake Chabot, the flow from the Sierras insures that Briones can hold 19.7 billion gallons of water relative to Lake Chabot’s 3.4 billion gallons.

L191-25-Herrington-Olsen Photo, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 138476cv, (Image 6 of 40)

Lafayette Reservoir is the only other large East Bay reservoir completed by EBMUD, and the year was 1928. This south view of the reservoir is from 1939. This reservoir and Lake Chabot were the first opened for recreational use in 1966, and, in addition, these no longer serve as primary terminal reservoirs. Ref: Commercial and Photo Co. Photo, 516 13th Street, Oakland

L191-30-Courtesy East Bay Municipal Utility District, P-TR-716 or EBMUD 278, (Image 7 of 40)

This informative figure shows which of the privately-owned lands of the EBWC went to EBMUD versus land that was retained. The 832 acres of land for Briones which was mostly in the East Bay Water Co. hands in 1928, shown as “no.1”, was acquired in the early 1960s from 28 property owners, 7 of whom tried to stop the sale in court. Ref: G4363 A3646 1920.L3

L191-35 Courtesy Earth Sciences and Map Library, University California, Berkeley , (Image 8 of 40)

Although competed in the 1926-27 timeframe, Upper San Leandro Reservoir was constructed by privately-owned EBWC. EBMUD was still not empowered by bonds to acquire the land or build it at this time, nor did they have the personnel to initiate this. Northeast view, June 3, 1925.

L191-40-Eston Cheney Photo W-759, John Bosko Collection, Courtesy John Bosko, (Image 9 of 40)

EBWC built San Pablo Reservoir in 1918-1919 as WWI had resulted in a doubling of ground water usage. It was the first of the large terminal reservoirs of the 1900s. As seen in this northeast view from Nov. 29, 1924, significant amounts of water are only present by the dam in the distance as the ongoing drought prevented it from filling until EBMUD supplied Sierra-based water in the early 1930s.

L191-45-Eston Cheney Photo W-646, Herrington-Olsen Collection, Courtesy BAERA, WRM Archives, 132665c, (Image 10 of 40)

The Figuers’ report states that groundwater supplied 30-100% of the water used in the East Bay between 1860-1930. Once EBMUD took over, except for thousands of residential private wells, ground water pumping was restricted to the Alameda County Water District’s efforts to supply Newark and parts south. The land to the north of Oakland Airport shown here in the late 1920s was the Fitchburg Well Field, one place where continuous groundwater pumping had taken place. Ref: API 654_6_BOX 91

L191-50-George Russell Photo, Courtesy California State Lands Commission, (Image 11 of 40)

Based on data contained within Figuers’ report, the EBWC map has been modified to show the major water sources in 1911 and the percentages out of 100% for various categories or specific sources. There were also other smaller water sources and approximately 3841 active private wells. The over pumping of ground water sources as war and drought followed resulted in salt intrusion and loss of water supply in many cases. Ref: G4363 A3646 1920.L3

L191-55-Courtesy Earth Sciences and Map Library, University California, Berkeley , (Image 12 of 40)

EBWC bought out the last competitor in the private “Water Wars”, the Union Water Co. of 1910, on Oct. 27, 1921. Its wells spread from Richmond to Newark. In Oakland, its Kinsell Well Field, Jones Ave. Well Field, and Walker Well Field were situated at about 98th St., then Jones Ave., in what was called Elmhurst, seen here in a northwest view in the late 1920s. Ref: API 651_61_BOX 91 thru 95

L191-60-George Russell Photo, Courtesy California State Lands Commission, (Image 13 of 40)

The EBWC came into being in 1916 as its predecessor, the People’s Water Co., PWC, had both financial and operational difficulties as the population doubled during their tenure. PWC was incorporated on Aug. 30, 1906, and Noble comments that PWC’s legacy was in introducing metering of water use that resulted in decreasing per capita water consumption by half. Prior to this, water rates had been determined by the size of the home, the number of tubs, toilets, and hoses, and number of residents.

L191-65-Realty Bonds and Finance Co.Map, Courtesy John Bosko , (Image 14 of 40)

Havens and his business partner “Borax” Smith had created the Realty Syndicate in 1895, and by 1906 it had amassed 13,000 acres of the Oakland hills. The Syndicate Water Co. was incorporated on Jan. 1, 1906, and as reported in June 11, 1906 New York Times, they were to add the 19th century-dominant, but financially strapped, Contra Costa Water Co., and two post-1900 additions, the Richmond Water Co. and Bay City Water Co. The combined result was renamed the PWC. Havens and Smith split their holdings soon thereafter, with Havens retaining most of the hill property while serving as PWC president until it was reorganized to the EBWC.

L191-70-Woodward, Watson and Co. Map of Oakland, John Bosko Collection, Courtesy John Bosko, (Image 15 of 40)

A detail of the 1903 map shows the casualties of the late 1890s “Water Wars”, primarily between William Dingee’s Oakland Water Co., OWC, originally the Piedmont Springs Power and Water Co., PSPWC, of 1891, and Anthony Chabot’s Contra Costa Water Co. of 1866. The roots of war started when a law was passed in California in 1858 to allow water companies to force the sale of land they claimed they would use to supply water, as long as they also promised to supply water to fight fires for free.

L191-75-Woodward, Watson and Co. Map of Oakland, John Bosko Collection, Courtesy John Bosko, (Image 16 of 40)

Engineering marvel Anthony Chabot’s Contra Costa Water Co.’s centerpiece was San Leandro Reservoir of 1876, renamed Lake Chabot after his death in 1889, pictured in 1916 in a northeast view. At the time, it was the highest earthen dam in the world. Although the company dominated the water industry until his death in 1888, it continually faced problems with water quality and quantity.

L191-80-Sappers Collection, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 115003ov, (Image 17 of 40)

Chabot got started by using creek water in 1866, but timely political interference and failure to deliver by other local water interests gave him the opportunity to complete Lake Temescal and the associated dam at it’s far end in the 1868-1869 timeframe as seen in this northwest west view, circa 1913. Figuers states that the reservoir was active until 1930.

L191-85-Eston Cheney Photo B-1317, Sappers Coll., Courtesy BAERA, W. Railway Museum Arch., 24145sn, (Image 18 of 40)

Lake Temescal’s appeal was the large number of creek feeders, orange, relative to that for adjacent Harwood Creek, purple, or Shepherd Creek, black. CCWC’s shortcomings after Chabot death, however, would provide opportunity. Addition of filtration systems in the early the 1890s did not solve water quality issues. Even more important was that all that needed water could not be served.

L191-90-Woodward, Watson and Co. Map of Oakland, John Bosko Collection, Courtesy John Bosko, (Image 19 of 40)

William J. Dingee needed water for his Fernwood estate in Montclair, but was rebuffed by CCWC. That turned out to be a big mistake for CCWC. He turned to Chabot’s ex-engineer, William Boardman, who built seventeen tunnels toward the ridge line. Pipes brought all this together at Thorn Rd., now Thornhill Drive. West view, circa 1925.

L191-95-Cheney Photo H-1975, Oakland Cultural Heritage Survey, Oakland City Planning Department, (Image 20 of 40)

While Temescal Creek’s feeders would eventually curve to the northeast away from the road, Dingee’s tunnel system continued along the road past the intersection with what is today Moraga Ave., destined for his reservoir in Piedmont. The Sacramento Northern trestle over Thornhill Dr., seen in the left-center portion of this west view, points to the direction of the water’s flow. West view, May 22, 1932.

L191-100-Eston Cheney D8959A, John Bosko Collection, Courtesy John Bosko, (Image 21 of 40)

A detail of the 1903 map shows the general expanse of Dingee’s original tunnels. Although not mentioned, their placement must have encroached upon the supply to Temescal Creek. The initial reservoir where water came together was called Kohler Receiver, and was located near where Pinehaven Rd. meets Thornhill Dr., but to the east of the latter road.

L191-105-Woodward, Watson and Co. Map of Oakland, John Bosko Collection, Courtesy John Bosko, (Image 22 of 40)

The tunnels Boardman designed for Dingee into the hillside ranged from 45 to 400 feet in depth. The northeast view from 2019 on the left shows the land above the end of Sobrante Rd., the original path of the Thorn Rd. from the ridge line. In the right panel, a small creek running along the eastern side of this section seen at the end of Sobrante Rd. disappears from view. Whether a stream like this contributed to Lake Temescal or Dingee’s output is unknown.

L191-110-Stuart Swiedler Photos, (Image 23 of 40)

A major feeder to Temescal Creek is still exposed along Pinehaven Rd., seen here in 2019 close to its exposed origin looking toward the source on the right, and the flow toward Lake Temescal on the left.

L191-115-Stuart Swiedler Photos, (Image 24 of 40)

On the left, heading downhill on Sobrante Rd. to where it meets Thornhill Drive, a bridge over the exposed second major arm of Temescal Creek in this area is located just east of where Heather Ridge Way meets Thornhill Dr. This exposed section of creek joins the one from Pinehaven Rd., and the combined output can be seen flowing downhill through the Thornhill Nursery on the right. Both photos, 2019.

L191-120-Stuart Swiedler Photos, (Image 25 of 40)

Many of Dingee’s tunnels failed within a decade, but Fuguer’s report notes that many streams were diverted to make up for those losses. For those contemplating tunnel discovery, it is also reported that EBMUD plugged these tunnels with cement between 1945-1954. This southeast view along the Oakland, Antioch and Eastern’s right-of-way with the lighter area between the tracks marking the trestle over Thornhill Dr. shows how undeveloped the area was circa 1913.

L191-125-Eston Cheney Photo B-1306, Sappers Coll. Courtesy BAERA, W. Railway Museum Arch., 24131sn, (Image 26 of 40)

This southwest view circa 1928 from the top of Piedmont shows what today is called Dingee’s Reservoir, where his early tunnel’s output was stored. According to Noble, CCWC had already enticed the surrounding Piedmont customers into long term contracts prior to this supply being available.

L191-130-Aerograph Photo Co. Photo 58101, Courtesy East Bay Municipal District , (Image 27 of 40)

Acknowledgement and appreciation to Tim Parkyn for providing the annotated image showing that the reservoir in the image is not Dingee’s Reservoir, that structure off the image to the right, and for suggesting the use of the 1892 map published by Dingee showing the location of his tunnels in the hills. Ref: Left, Aerograph Photo Co. Photo 58101, Courtesy EBMUD; Right, Courtesy EBMUD and Earth Sciences and Map Library, University California, Berkeley, G4364_O2_1892_M61_100, Map of Oakland and vicinity. Compiled from official surveys and records by T.W. Morgan et al. Published Oakland, Calif. : William J. Dingee, 1892 H.S. Crocker Company

L191-132-Courtesy EBMUD and Earth Sciences and Map Library, University California, Berkeley , (Image 28 of 40)

Undeterred, Dingee sent his pipes down the slopes of Piedmont into Oakland to 25th St. He would secure more capital in 1893, and renamed his company the Oakland Water Co. to signal his new and larger target, and all-out war with CCWC. He expanded his reach by constructing two well fields in West Oakland, and would soon gain hold of the Alavarado Well Field. Northeast view, circa 1930. Ref: pAPI 651_54_BOX 91 thru 95

L191-135-George Russell Photo, Courtesy California State Lands Commission, (Image 29 of 40)

Dingee fought with CCWC over distribution in the East Bay, and hampered each others operations until they were forced to merge in the clutches of drought in 1899. He retained control, and made a fortune that he would eventually lose. His innovative thinking created competition with CCWC forcing better quality and service. One of the great mysteries was why Dingee did not just tap into Temescal Creek to feed his garden as it passed through his property as shown in the 1903 map, although the creek was not exposed at that time.

L191-140-Woodward, Watson and Co. Map of Oakland, John Bosko Collection, Courtesy John Bosko, (Image 30 of 40)

In 2019, Temescal Creek remains exposed from the Fernwood area all the way to Broadway Terrace, much to the credit of the Percy family who unearthed the creek in the 1900s on the land where Fernwood had stood before it burned in 1899. To summarize “Water Wars” best, the companies involved could never charge enough to cover their costs, with pricing largely determined by the Oakland City council. Dingee’s success in the 1890s forced water rates down such that competition sought merger to stay in business.

L191-145-Stuart Swiedler Photos, (Image 31 of 40)

When Broadway Terrace was reconfigured in 1936 with the expansion of the former Quercus Ct., a culvert was built for Temescal Creek, left, such that the creek did not become visible again until in Lake Temescal Park. The last chance to see the creek south of the park is still at the white fence on the south side of Broadway Terrace, shown here on July 21, 1941.

L191-150-Eston Cheney Photo D-9170, Courtesy John Bosko and Public Works, OCHS, Oakland City Plan., (Image 32 of 40)

The second major feeder to Lake Temescal is marked by the blue arrow on the 1903 map. It appears that CCWC had no competitors for this supply.

L191-155-Woodward, Watson and Co. Map of Oakland, John Bosko Collection, Courtesy John Bosko, (Image 33 of 40)

A southeast view down the right-of-way of the Oakland, Antioch and Eastern Railway circa 1913 shows where the feeder just discussed emptied to the east or left of the railway overpass. The sign in the background is for sale of lots in the Claremont Chabot Tract.

L191-160-Eston Cheney Photo B-1323, Sappers Coll. Courtesy BAERA, W. Railway Museum Arch., 24157oae, (Image 34 of 40)

A west view of the same overpass, circa 1913.

L191-165-Eston Cheney Photo B-1322, Sappers Coll. Courtesy BAERA, W. Railway Museum Arch., 24156oae, (Image 35 of 40)

Shown here is the small eastern arm of the lake where the additional creek waters emptied. Note the presence of Tunnel Rd. indicated by the guard rail in the above hills.

L191-170-Eston Cheney Photo B-1314, Sappers Coll. Courtesy BAERA, W. Railway Museum Arch., 24140oae, (Image 36 of 40)

Construction in 1935 of the extension of Broadway to access the new tunnel with Contra Costa County meant the end of the eastern arm of the lake and for the need of a railway bridge. The majority of the open creek was set in a culvert according to Janet Sowers creek maps at www.acgov.org/aceh/lop/Oakland-Berkeley_Creek_Map.pdf

L191-175-HJW Geospatial Inc., Pacific Aerial Surveys, Oakland CA, Courtesy E. Bay Regional Park Dist, (Image 37 of 40)

Lake Temescal seen here in an east view on May 18, 1940 became one of three centerpieces of the East Bay Regional Park District’s acquisition from EBMUD of 2162 acres on June 4, 1936. Much appreciation to John Bosko for providing so many important images, and to David Gowen for his overall input and supplying important reference materials.

L191-180-Courtesy Arnold Menke and Garth Groff, (Image 38 of 40)

Additional images will added in the future such as this north view of Alameda from the early 1920s based on the presence of both the Webster and Harrison St. bridges in the background. According to Figuers, Alameda had a good water supply from individual wells. The Alameda Water Co. of 1874 was the first significant enterprise, and in 1879 it was purchased by the Alameda Artesian Water Co. It would be acquired by CCWC in 1899, and the island subsequently received water from Oakland’s Fitchberg Well Field. Ref: API 639_1_BOX 95

L191-185-George Russell Photo, Courtesy California State Lands Commission , (Image 39 of 40)

A separate Alameda Water Co. supplied Berkeley from 1885 until its sale to CCWC in 1900. This 1935 north view of UC Berkeley is a reminder that the College of California supplied its own water from Strawberry Creek from 1866 at the foot of Panoramic Way near Memorial Stadium until they sold it to H.B. Berryman and partner in 1869. Although out of the water business for the city, the University would later explore for water for its own needs on multiple occasions. See Ruth Kondor’s paper at nature.berkeley.edu. Ref: USNPS-5-G 1935

L191-190-HJW Geospatial Inc., Pacific Aerial Surveys, Oakland CA, Courtesy E. Bay Regional Park Dist, (Image 40 of 40)